Social philately is becoming increasingly important among collectors. It’s not (only) the postal item that matters, but also the sender, the addressee, and possibly the content of a letter. Sometimes, the social aspect is more significant than the letter itself, and a letter without a ‘social background’ could hardly be considered collectible. How different it is with the letter discussed here. The family history of a family unknown to you typically wouldn’t interest you. Yet, it’s worth reading on, even if you’re neither related to the Boom family nor know a true Boom.

Our Booms

The common thread in ‘our’ Boom family is chemistry and printing. We go back to the year 1769, the birth year of Gerrit Otto Boom (1769-1835), a pharmacist in Almelo. Like most Booms in our story, he had a large family. Two sons are of interest to us: Bernardus (1800-1875, pharmacist in Almelo) and Jan Adolf (1803-1893, pharmacist in Meppel).

Rare Combination

Jan Adolf, born in Almelo, obtained his pharmacist’s diploma in Assen and established himself as a pharmacist in Meppel in 1825. Alongside his pharmacy, Jan Adolf ran a small chemical business that primarily processed plants and herbs. In 1841, Jan Adolf became co-owner of a small printing business, which, among other things, started publishing the Meppeler Courant from 1845. Evidently, his love for the printing trade was greater than for chemistry, and in 1859, Jan Adolf bid farewell to chemistry.

Trade in Paper?

Unfortunately, evidence for this has yet to be found. However, it wouldn’t be illogical for Jan Adolf to see potential in (special) types of paper. Whether for the printing business or the chemical branch, both required paper. It seems that Jan Adolf was an importer or agent for a well-known English paper firm, specializing in unique kinds: the Bathford Paper Mills, now owned by De La Rue, a name not unknown to philatelists like us.

Bath

In the 19th century, writing paper (letter paper) from Bathford was widely available in many countries, including the Netherlands. It was marketed under the brand name BATH and was embossed with a dry stamp, of which many variants exist.

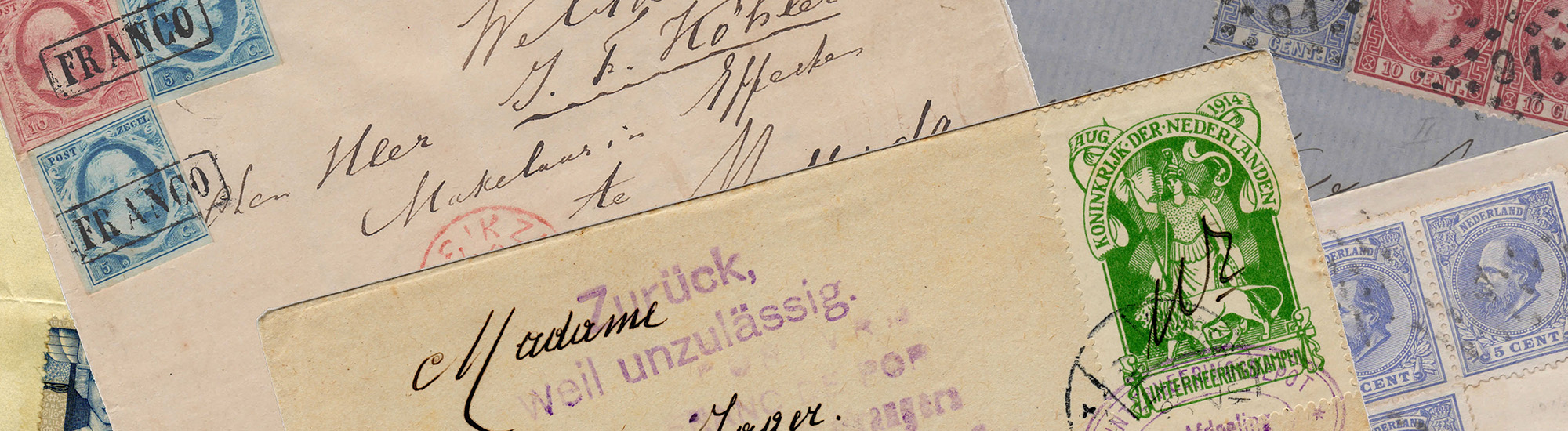

There is (only one known) a dry stamp BATH found in a 10c stamp from the 1852 issue. Other dry stamps are not known for this issue. The stamp with the dry stamp is attached to an envelope: a genuine envelope.

Family Correspondence

The letter was – presumably – sent by Jan Adolf from Meppel on the 22nd of April 1858 to his brother Bernardus, the pharmacist in Almelo (arrival stamp on the 23rd), who was staying with his (unmarried) aunt Gesina at the time. As a sort of precursor to a perfin (a company perforation on a stamp), he evidently wanted to build in some security against the misuse of the expensive stamp of that time. Possibly inspired by England (where dry stamps on stamps had been used since 1847), he affixed the stamp to the envelope and, likely as a trial, embossed it with a dry stamp BATH. There’s no doubt that the dry stamp impression was made after the stamp was affixed (embossing through to the back of the envelope and before cancellation, with uneven ink distribution due to the height difference caused by the dry stamp). Since two nearly identical envelopes are known (also franked with 10c, same correspondence, poor quality, also with the Meppel circular stamp, but without the dry stamp), there’s no doubt about the authenticity of this correspondence.

Dry Stamp: Security!

That dry stamps offer some – even if limited – security is clear. Hence the term security embossing is used. We, of course, know dry stamps in fiscal paper and later as dry seals.

As mentioned, individuals in England were already using dry stamps on stamps by 1847, as a precursor to the perfin. In the United States, there’s even a notice in the New York Times of December 21, 1862, titled “Embossing Postage Stamps on Envelopes and Paper for Private Parties.”